Chapter 2 | Data and Methods

The primary goal of this analysis is to understand variations in the experiences of “Downtown America”, a qualitative phenomenon that we attempt to capture with quantitative measures below. The aspects of urban vitality that we need to put numbers on are aspects of built form—how large are the builings and how narrow are the streets?—and natural enviromment–is this area treed or untreed?—along with how many people are around. Fortunately, we have access to estimations of all of these components from free and open sources.1

forms

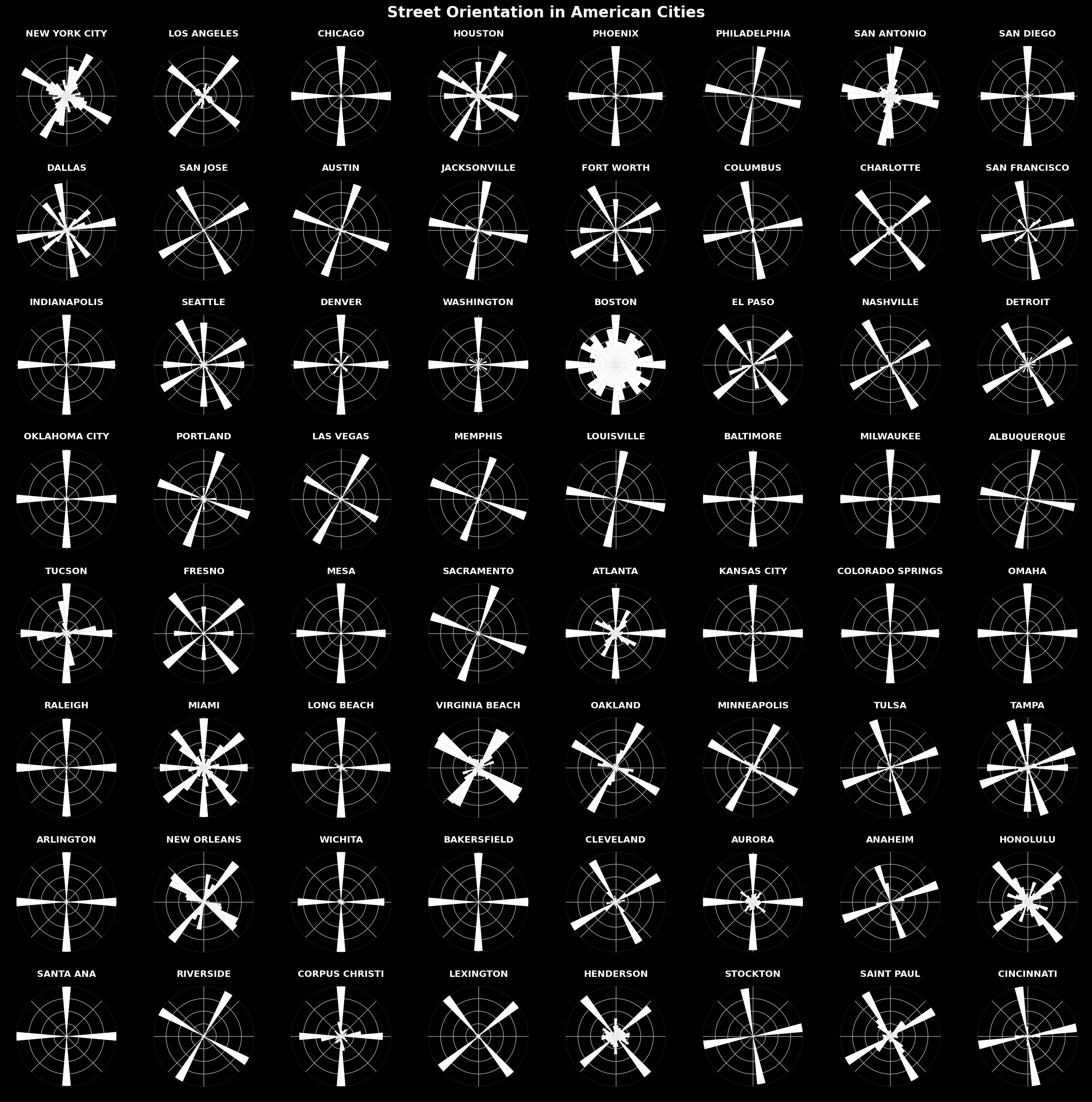

We begin by using the osmnx package in Python along with several unique scripts to call OpenStreetMap and request data on several of the necessary variables. Specifically, OpenStreetMap has information on roads and buildings and osmnx has several functions that convert these data into graphs for further analysis. We take the latitude and longitude of each downtown and construct a box of 1000 meters in each direction from this point (2000 by 2000 meters). We extract from OpenStreetMap the road networks within each bounding box, converting it into a graph of nodes and edges, along with building footprints. With these nodes and edges we can compute several metrics, including orientation, circuity and length of streets. Below we show the binned orientations of streets from a sample of cities in our list, made with help from a paper and replication files from Geoff Boeing.

Street bearings

Circuity of streets, size of intersections, and orientation all measure a grid-mess continuum: is a city a grid or a mess of streets? A city with straight roads that never or rarely end at intersections and are oriented in one of two ways is a perfect grid. We use these measures ot construct a grid index, also based on a paper and replication files from Geoff Boeing; grid index is the geometric mean of straightness, fourway rate, and orientation order, after each of them has been rescaled from 0 to 1. Because our grid index weights each measure equally and circuity had little variance (since we limit ourselves to downtowns), we remove that from the index but store it as a measure for future study.

We can also calculate the fractal dimension of a city by exporting street network or building footprint maps as images and calculating what is called Minkowski–Bouligand dimension. Based on freely available code, this method looks at how easy it is to cover a shape with different sized boxes.

Fractal dimension using streets and buildings

This gives an important measure of the character of a place: namely, how repititious it is. We see above that the highest fractal dimension using buildings is Cambridge but the highest using streets is Denver; many other grid cities feature. This measure can be driven by artifacts in the data. In OpenStreetMap, users can map footpaths separate from motorways, but not all do, so a few cities have roads in triplicate—a footpath on either side with a motorway down the middle. This will artificially inflate fractal dimension: each street appearing three times is indeed repetitive. Further, buildings are less populated in OpenStreetMap than streets, so fractal dimension here will be deflated. We use the mean of both these fractal dimensions to mitigate these issues.

populations

The Oak Ridge National Laboratory provides estimates on 100 meter grid cells of population during both day and night times based on remote sensing. Using the squares that we contruct above, we can extract mean and standard deviation per tile. We limit ourselves to these zonal statistics because the data are vast and prohibitive to manipulate locally: the United States is comprised of many 100 by 100 meter cells. Instead we use the Earth Engine Python interface to do much of these computations in the cloud. Earth Engine can perform several but we are looking for those that describe the character of a place, and whether it contains a large population or it has both sparse and dense areas are relevant to this goal.

Population by day and night

We can see that some areas hold large daytime populations and others hold large nighttime populations: Chicago’s downtown is home to more people during the day than any other city in America but Cambridge has more people by night.

environments

To capture the role of the natural environment in a city’s feel and form, we look at both water and plants using common indices calculated from satellite imagery. Normalized differences are simply the different between two bands divided by the sum of those two bands; the results, depending on the band, can illuminate different aspects of an image, including whether it contains plants—which emit infrared radiation—and whether it contains water. They are not perfect, but areas with much vegetation will tend to have a high normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and areas with large bodies of water will have a high normalized difference water index (NDWI). The importance of NDVI toward the character of a place is manifest in temperature and in look, but the value of measuring NDWI is perhaps less obvious; some cities are situated on large bodies of water and—as in the case of Miami—this is part and parcel of its character. osmnx also allows us to acquire elevation data and street gradients, which indicate how hilly an area is—another important component of urban feel: few would say that San Francisco and New York are the same, even though they both have downtowns with tall buildings and gridded streets.

results

The resulting dataset contains the variables shown below. Some will be directly relevant to our construction of similarity scores and clusters in the following section and others were produced during the above calculations and may be of use in later research. We plot it as a correlation matrix to see how the variables interact. Some associations are intuitive, with edge length at odds with the number of nodes, but others run counter to intuition: building size is negatively correlated with nighttime population—as one might expect with office towers as large buildings that empty out—but only weakly so—and the relation does not invert for daytime population.

Final dataset

From these variables we derive grid index (as above), mean building/street fractal dimension, mean NDWI/NDVI, mean street length/building size and the interquartile range of street grades. This is the processed data that we will use in the cluster and related analyses that follow.

Resulting variables

-

None of our data are perfect: OpenStreetMap is maintained by a robust community but its members are not ubiquitous and some parts of the country lack coverage; gridded population data is derived from machine learning and uses built form, night lights and other variables to form an estimate. ↩

Updated: